You sit across the table from your client, your favorite pen poised over your favorite notebook, quietly trying to broadcast your thoughts into his brain. “Please don’t say it, please don’t say it…” A childlike expression passes over his face like a cloud before he speaks: “I like the design…but can we make it interactive?”

Before you lament how a nation overflowing with Internet access has trained us all to crave interactivity in everything, it might help to take stock of just how many ways you can make your print project interactive today. You might even discover a way to make a good design fantastic.

Cutting-edge interactivity

The technology that allows us to bring our paper creations to life has changed dramatically over the years. And there are even more dramatic changes still to come.

Take the possibilities of bringing electronics to the printed page. Already artists are experimenting with “conductive” inks that can literally print electronic circuitry onto ordinary paper.

French industrial designer Jean-Sébastien Lagrange recently produced a poster that emits enough light to act as a lamp, simply by printing connective lines between LEDs using a standard inkjet printer. Once the poster is attached to a power source, it lights up. And there’s no reason that a web-fed inkjet printer couldn’t be modified to print using conductive ink. (For those wanting to experiment with the medium, a small company called Bare Conductive sells a pen that allows you to hand draw circuits on any surface with conductive ink.)

Ever on the cutting-edge, Arjowiggins has recently developed and marketed a paper called PowerCoat that refines this idea even further, offering a substrate smooth enough to allow complex circuitry to be printed directly onto it.

Because of its high cost, the paper is currently pitched as a replacement for thin plastic film, and geared more toward printing things like keyboard circuitry and aerials for the radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags now used for tracking everything from livestock to military supplies. However, like most technologies, chances are good that the costs of producing the paper will come down.

What, then, is the real design potential for conductive-ink printing? Virtually limitless: Packaging and brochure covers that light up and play videos, music, and most importantly, interact. Suppose a magazine has on its cover a small keyboard from which people can email your client directly requesting more information about their product, simply by using their office Wi-Fi connection?

That’ll never happen, you say? It’s already been done…and was accomplished using an even older technology: SMS.

The other ‘sexting’: Sales texting

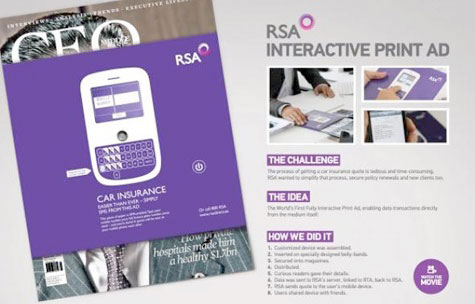

The print-interactivity experiment OgilvyOne came up with for Middle Eastern car insurance company RSA was an impressive example of rethinking the technology we already have. Rather than simply claiming that their rates were the lowest in Dubai, RSA partnered with the agency to create a cardboard cover that was slipped over 100 copies of CEO Middle East magazine.

On the front, an illustration of a BlackBerry-like device…but the buttons on the device actually worked. Readers were encouraged to send their car details to RSA using this print piece – the information was relayed by SMS, the technology that allows you to send a text message from your phone.

“The device we custom built for this campaign,” OgilvyOne’s regional creative director, Fabian Roser, told PaperSpecs earlier this year. “It is SMS-enabled, and contains a prepaid SIM card. Hence the initial details, keyed in from the readers of the magazine, are submitted to RSA via SMS. No Internet-connection needed!”

Shortly after submitting their info, users received a customized price quote for insurance. The result: 63 new insurance policies and eight renewals.

Should I have my reality augmented?

From the cutting edge we go to one of the industry’s most-used buzzwords today: augmented reality, or AR. Though often used interchangeably with discussions of QR codes, AR is a more sophisticated beast. (Grab a cup of coffee, here comes the explainy bit…)

With QR codes, you include a type of complex barcode somewhere in your printed piece. By scanning the code using a special app on their smartphones or tablet computers, readers are treated to pre-selected videos, text or images, or sent to a website.

With augmented reality, a reader examines the printed piece directly through the camera on their smartphone or tablet. However, what they see on their screens are videos, images and/or text that is superimposed over what their camera is trained on, “augmenting the reality” of the printed page.

Most commercial uses of the technology have been pretty lackluster so far, treating the print piece as little more than an unnecessary trigger for an audio-visual experience on people’s iPads – why not just make these things iPad apps? However, there have been some pretty interesting exceptions to this.

- Esquire’s December 2012 issue: Along with playing videos and allowing readers to share articles via social media or text message, the associated app allowed readers to digitally “clip” articles from the print issue, and organize them for later reading.

- The Office Turntable: (Technically this is a QR code piece, but blurs the line thanks to what it actually does.) Germany’s Kontor Records sent out a promo vinyl record in a special envelope. When refolded, the envelope became a mock turntable. And when the user scanned a QR code with their smartphone and then rested it on the album, a video played on the screen that gave the illusion that the record was spinning on the turntable, and music played.

Yet the most effective use of AR to date has been IKEA’s 2014 catalog. After scanning a piece of furniture in the catalog with your device, your screen then shows you how it would look in any part of your home – a perfect marriage between print and technology.

Paper interactivity

Technology is all well and good, but any designer likely feels that paper is interactive enough on its own, and rightly so. All that is required is a little imagination.

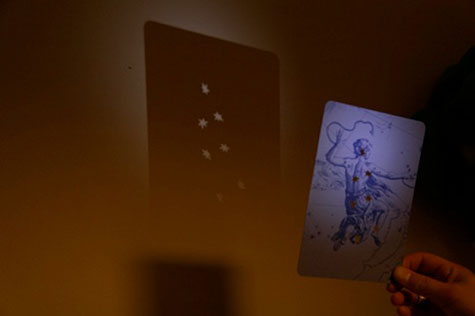

Just this year we’ve seen business cards that fold out into 3D office scenes, an otherworldly poster that plays with the light, and so much more.

However, one of our favorite examples of interactivity remains a 2001 children’s kit from Chronicle Books called “Seeing Stars” by Charles Hobson. Inside the cardboard box we find a thin flashlight, a 48-page guide to constellation mythology, and 10 diecut cards, each depicting a constellation. Turn out the lights and shine the flashlight through the star-shaped holes in each card to see that constellation perfectly duplicated on your wall.

Now that’s stellar paper interactivity.

………